Well, it finally happened—the yield curve inverted. Now note that it was the shorter end of the curve that inverted, as the 3-month Treasury bill (and 1-year T-bill) now yields more than the 10-year Treasury for the first time since 2007. This matters because an inverted yield curve is the bond market’s way of saying there is a potential recession on the horizon. “The yield curve inversion is something that nearly everyone is talking about, given its perfect track record at predicting recessions,” explained LPL Senior Market Strategist Ryan Detrick. “At the same time, however, we simply aren’t seeing other areas of the economy that would confirm a recession just yet, so there is more to this story.”

Please note that there is no one true “yield curve,” as the yield curve simply looks at the yields of a shorter-dated fixed income instrument and compares it to a longer-dated one. In fact, the more commonly discussed 2-year/10-year yield curve spread hasn’t inverted, and it is actually above the early December 2018 lows.

Here are 11 things worth considering regarding the yield curve.

- Each of the past 9 recessions back to the 1950s saw the 1-year/10-year yield curve spread invert approximately 14 months on average before a recession.

- Although a yield curve inversion preceded all 9 previous recessions, not all inversions led to a recession. For instance, the 3-month/10-year yield curve inverted in 1966 and 1998, with neither leading to an immediate recession.

- The shorter end of the yield curve has inverted, but the longer end is actually steepening. For instance, the 10-year/30-year yield curve has steepened most of this year. In past recessions, all parts of the curve inverted before a recession took place.

- Financial conditions aren’t tight, as tight conditions coupled with the yield curve inverting, historically has led to a recession. Investment-grade corporate and high yield spreads remain calm, however, suggesting that not all parts of the bond market are worried about an impending recession.

- Market participants have fully priced in a Federal Reserve (Fed) rate cut within the next year, potentially further flattening the curve. Should the economy gain steam during the second half of this year (which we think is possible) it will likely avoid a Fed rate cut, which should lead to a steeper yield curve.

- We have found that a spread between the 3-month/10-year yield curve has become much more predictive of a recession at -50 basis points (-0.50%). So this still is a clear concern, but a marginal inversion may not be so worrisome.

- Yield curves aren’t always perfect: Japan has had long stretches of inverted curves that didn’t lead to recessions. Additionally, both the United Kingdom and Germany have had inversions without recessions.

- The fed funds rate has been significantly higher during previous inversions. In fact, the fed funds rate has averaged more than 6% when the 1-year/10-year yield curve has inverted. It is only 2.4% currently.

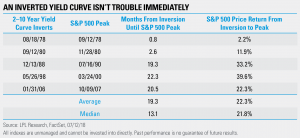

- The previous 5 recessions began an average of 21 months after the 2-year/10-year yield curve inverted. Stocks actually did quite well initially after inversions as well, with the S&P 500 Index not peaking until over a year after the inversions and gaining nearly 22% on average at the peak.

- Various yields around the globe continue to sink, with nearly $10 trillion in global debt now yielding less than 0%. The German 10-year Bund, for instance, is beneath 0% for the first time since 2016. We think this is due more to a concern over the European slowdown, which has forced many to look to the United States as a safe haven for sovereign debt, thus pushing our yields much lower along the way. This concept is discussed in more depth in our latest episode of the LPL Market Signals podcast.

- As our LPL Chart of the Day shows, the S&P 500 has actually outperformed the average year the previous three times the 2-year/10-year yield curve inverted. To reiterate though, the 2/10 spread hasn’t inverted yet.

In summary, an inversion on part of the yield curve may suggest trouble ahead for the economy, but don’t forget that economic growth and potential stock market gains can continue for years after the initial inversion. Additionally, with credit markets holding up well, employment still strong, and wages still increasing, we don’t yet see the necessary combination of worries that could suggest a recession is indeed imminent.